O nieśmiertelności prawdy

Drodzy Słuchacze Akademosa!

Nadchodzą święta. Wierzący chrześcijanie, z wiadomych powodów, radują się, większość innych osób, niejako równolegle, w taki lub inny sposób świętuje. Każdemu z nas jednak, niezależnie od światopoglądu, zdarzają się przecież refleksje nawiązujące do tego, jakże trudnego do pojęcia wydarzenia.

Zadaję sobie pytanie, czy na co dzień można zetknąć się ze zjawiskiem nieśmiertelności i muszę stwierdzić, że owszem, nawet często. Chodzi mi o nieśmiertelność ducha, idei. O nieśmiertelność prawdy, tego, co czasami trudno uchwytne, co mimo pozornych klęsk jednak potrafi w nas przeżyć.

Podam przykład ze swojej przeszłości. Tak się złożyło, że kilkadziesiąt lat temu, podjąłem studia w Wyższej Szkole Języków Obcych UW, swoistej antytezie wydziałów filologii, przygotowujących wówczas do wszystkiego, tylko nie do nauczania języków lub tłumaczenia ich. Studium powstało wokół mądrej, praktycznej koncepcji, że krajowi potrzeba mniej naukowców, zgłębiających zawiłą istotę języka na przestrzeni dziejów, a raczej ludzi, władających dobrze językiem współczesnym. Źródła tej koncepcji wybiły w Poznaniu (UAM), wówczas najsilniejszym ośrodku językoznawczym, i Warszawie.

Nauczane były 4 języki: angielski, francuski, niemiecki i rosyjski, przy czym studenci mogli wybrać sobie drugi język spośród wspomnianych ew. język hiszpański. Warto nadmienić, że język drugi był na wyjątkowo wysokim, jak na owe czasy, poziomie. Nic dziwnego zatem, że absolwentów zatrudniano niejako z „łapanki”. Deklasowali oni bowiem w większości swoich rówieśników z filologii.

Nie dziwi też, że Studium naszemu obrywało się od konkurencji i pod naporem tychże ataków zostało w końcu formalnie rozwiązane.

Wtedy stała się jednak rzecz zdumiewająca, bo na jego gruzach, dokładnie w tym samym miejscu, powstał Instytut Lingwistyki Stosowanej, którego kadra w dużej mierze wzięła się z “tonącego okrętu” WSJO. Sam miałem satysfakcję, jako młody asystent, uczestniczyć w powolnych, ale udanych narodzinach Instytutu.

A zatem duch WSJO przeżył, ponieważ Instytut, wzmocniony naukowo, w swoim kształcie programowym w niewielkim stopniu różni się od swojego poprzednika i do dzisiaj cieszy się chyba największym prestiżem wśród wydziałów językowych Polski. Natomiast trzęsienie ziemi, towarzyszące przeszłym wydarzeniom z biegiem lat sprawiło, że i filologie „opamiętały się”, dokonując syntezy idei i zmieniając zdecydowanie na lepsze swoje programy nauczania.

Pozdrawiamy i życzymy wesołych Świąt Wielkanocnych!

Marta Żak-Gajewska

Wojciech Gajewski

Easter eggs symbolism

Easter cannot be celebrated without eggs. It is a tradition coming from ancient times. In this newsletter I am wondering why particularly eggs and what is their meaning as well as the meaning of the symbols chosen as a decoration for Easter eggs.

Eggs as a symbol

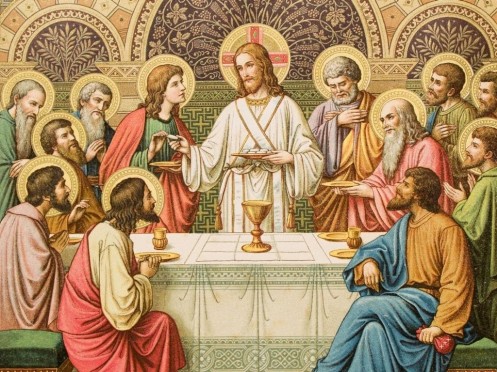

For many cultures, even before the time of Christianity, the egg was a symbol of creation, spring, and rebirth. After the resurrection of Christ, the egg took on a new meaning for Christians and became a symbol of new life breaking forth while leaving the empty tomb behind. Therefore, Easter eggs were shared with one another as a joyful symbol of Christian hope. Eggs were what helped people to understand a new theological truth, the resurrection of the dead, and a new religion Christianity built around the first Resurrection.

Mary Magdalene and the eggs

It is believed that this was due the account of Mary Magdalene who in fact used the egg to preach the Gospel to the Roman Emperor. When she met Tiberius, she held an egg in her hand and announced “Christ is risen!” The Emperor laughed at her and said that someone rising from the dead was as likely as the egg in her hand turning red. Of course, that is exactly what happened: the egg turned red and she continued to proclaim the good news to the imperial household.

Another story tells that Mary Magdalene went to the tomb early on the first day of the week, when the Sabbath was over, to anoint the body of Jesus. One tradition says that she took a basket of eggs with her to the tomb since she planned to stay there to mourn and would need something to eat. When she arrived at the tomb and uncovered the eggs, she found that the white eggs were now all the colours of the rainbow.

Easter eggs decorations

In the early days of Christianity, hen or duck eggs were painted, and each color had a meaning. Red meant the blood of Christ, ivory – the shroud, green – rebirth, blue – the peace of the Easter season, yellow – the early light of the day of resurrection, purple – the passion of Christ, the colour of Lent.

There is a whole vocabulary of the symbols which are used to decorate the eggs. Many of the symbols are universal, drawn from nature: the sun and the stars, flowers and fruits, leaves and trees, animals, birds and fish. A fish is an ancient symbol of health and also a symbol of Christ himself. A pine tree represents youth and health, as well as the Christian hope of eternal life. A rooster is a symbol of fertility.

Vocabulary

tomb – an excavation in earth or rock for the burial of a corpse; grave (grób)

resurrection – the rising of Christ after His death and burial (Zmartwychwstanie)

preach – to proclaim or make known by sermon (the gospel, good tidings, etc.) (propagować, głosić)

gospel – the teachings of Jesus and the apostles; the Christian revelation (Biblia)

emperor – the male sovereign or supreme ruler of an empire (Cesarz)

proclaim – to praise publicly (głosić)

anoint – to rub or sprinkle on; apply an unguent, ointment, or oily liquid to (namaszczać)

mourn – to grieve or lament for the dead (opłakiwać)

rainbow – a bow or arc of prismatic colors appearing in the heavens opposite the sun and caused by the refraction and reflection of the sun’s rays in drops of rain (tęcza)

hen – the female of any bird (kura)

ivory – of the color ivory (kolor kości słoniowej)

shroud – a cloth or sheet in which a corpse is wrapped for burial (całun)

rooster – the male of domestic fowl and certain game birds; cock (kogut)

lent – (in the Christian religion) an annual season of fasting and penitence in preparation for Easter, beginning on Ash Wednesday and lasting 40 weekdays to Easter, observed by Roman Catholic, Anglican, and certain other churches (okres postu)

pine tree – any evergreen, coniferous tree of the genus Pinus, having long, needle-shaped leaves, certain species of which yield timber, turpentine, tar, pitch, etc (sosna)